The weather was absolutely perfect. The famous Washington, D.C., mugginess was nowhere to be found as we landed at Dulles International Airport at 7 a.m. on a red-eye from Los Angeles. We blearily called an Uber and began what we thought would be a fight through D.C. rush-hour traffic to get to downtown Washington, but it was October and—compared to normal—the city was practically empty. With Congress out of session and both presidential candidates out on the campaign trail, it felt like we had the city to ourselves.

So when we arrived two hours earlier than expected at the Mayflower Hotel—one of the Grand Dames of the city and mere blocks from the White House—it wasn’t a surprise that only one of our rooms was ready. But the front desk didn’t bat an eye as they found another available room on the same floor within seconds. We breathed a sigh of relief—we had a busy few days ahead of us and desperately needed a nap. A few hours later, refreshed and ready to go, we began exploring the hotel and would discover it has one helluva story.

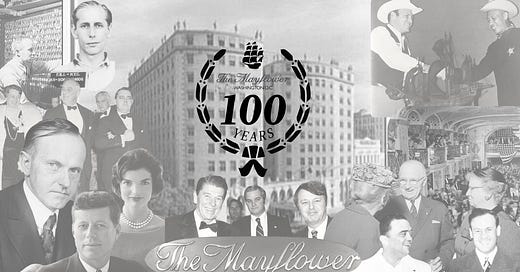

After a few initial setbacks and a name change, the Mayflower opened its doors on Feb. 18, 1925, to immediate acclaim and fanfare. It was a luxury hotel in every sense of the word, with private bathrooms in every room (almost unheard of at the time), air conditioned public spaces, and more gold trim than any building in the city except the Library of Congress.

The lobby’s grandeur was emphasized with wainscoting, Botticini marble, giant torcheres, and a coffered skylight to illuminate it all. The block-long Promenade was filled with sculptures and antiques, and the Grand Ballroom was outfitted in gold leaf and chandeliers for what would become some of the city’s grandest events.

The hotel made its mark on Washington’s social scene just two weeks after opening as the site of President Calvin Coolidge’s inaugural charity ball in its impressively outfitted Grand Ballroom. The Mayflower’s primary ghost story hearkens back to this event, as the Coolidges—who were still in mourning for a recently deceased son—did not attend the event.

But supposedly on Jan. 20 each year, the elevator holds on the eighth floor (where Coolidge would have emerged to make his debut) at 10 p.m. for about 15 minutes, then inexplicably heads down to the lobby—at the time the guests of honor were usually announced. Leftover plates of hors d’oeuvres have been found on the balcony of the ballroom—not strange in and of itself until the staff realized they didn’t resemble anything served in recent memory.

This has led many to believe Coolidge returns each year to attend his ball, despite the fact that his ball was held in March (the presidential inauguration was changed to Jan. 20 in 1937) and the fact that he didn’t want one in the first place (he thought spending public money on a ball was wasteful, so a group of private citizens actually paid for it, not the federal government).

Since we were staying there in October, not January, we breathed a sigh of relief that no ghosts would be hitching a ride with us in the elevator. But the ghosts of the past are everywhere you turn in the Mayflower. Almost every president, politician, and dignitary that has stepped foot in Washington, D.C., has had cause to walk its halls (or eat in its restaurants—it’s had quite a few over the years).

And speaking of restaurants, we had some truly unforgettable meals at Edgar Bar & Kitchen, located just off the Mayflower’s lobby. From the banana bread that has been on the menu since 1925 to the honey and vinegar short rib, every single meal we enjoyed there (and we enjoyed a lot) was the perfect balance of unpretentious but well presented, tasty, and filling.

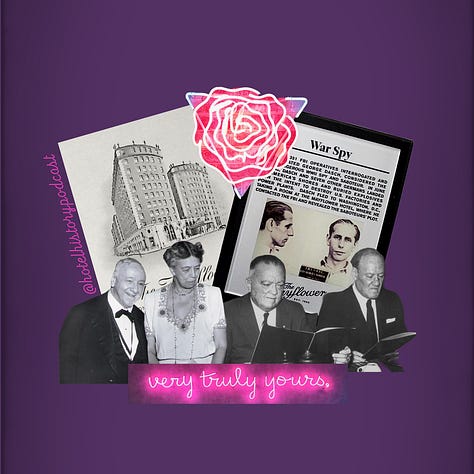

The restaurant, which includes a full service bar, is a little dark and moody on purpose—it captures the personality of its namesake, J. Edgar Hoover, the infamous FBI director who excelled and delighted in finding out (and, for the most part, keeping) secrets. Hoover ate at the Mayflower nearly every day for 20 years from 1952 until his death in 1972—naturally choosing a booth with his back to the wall and a good view of other diners.

The Mayflower also offers private dining at the Tolson Bird Bar, named for Hoover’s righthand man and rumored lover, Clyde Tolson (listen to part two of our series on the Mayflower for the tea on that whole situation).

The Bird Bar is bright and energetic—the opposite side of the Edgar coin—and features nice touches like framed prints of Tolson’s inventions, a doorway disguised as a bookcase, and nods to the LGBTQ+ community. The bar’s logo is a carnation superimposed on a pink upside down triangle. The carnation was popularized as a gay symbol by writer Oscar Wilde, while the pink triangle was reclaimed by the gay community in the 1970s after it was used to identify homosexual inmates of concentration camps during World War II.

And finally, the wall is decorated with a neon homage to Tolson’s (some would say romantic) sign off in notes to Hoover: “Very truly yours.”

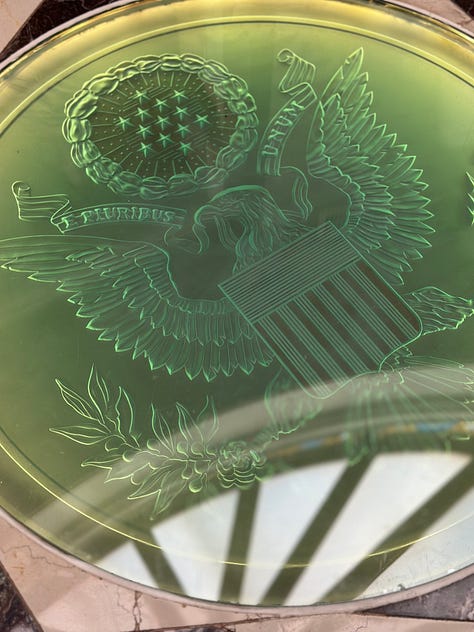

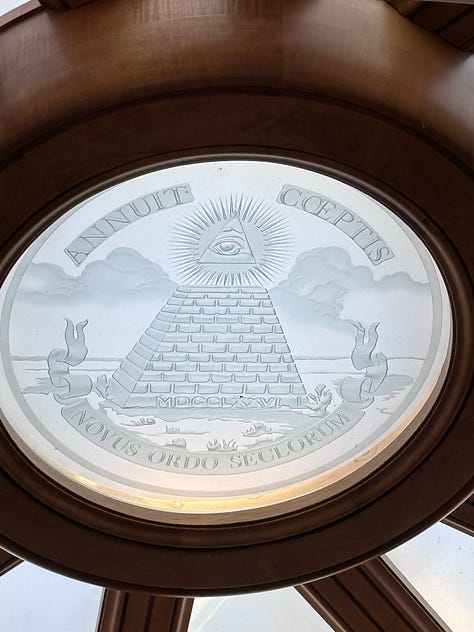

Traipsing around downtown Washington is no easy job (and we did traipse, only cheating a few times with Uber), so we looked forward to the short interludes spent in our rooms. The deluxe room was spacious enough that the king-sized bed and chaise longue didn’t feel imposing. The wallpaper is designed with celebrity signatures from the actual guest register, in case you forgot you’re staying somewhere history is made. (We suggest you upgrade to the Presidential Suite for a really swanky stay, assuming it isn’t currently occupied by a head of state. The stained-glass-rimmed skylight and Great-Seal-emblazoned floor in the foyer are stunning!)

While there, we interviewed a few staff members about what it’s like working in such a distinguished hotel. We’ll be sharing everything we learned in a video this spring (stay tuned and subscribe to our YouTube channel).

We also took some time to visit several other historic hotels in the area—check out our TikTok and Instagram profiles to see where we went along with lots more footage of the Mayflower. And in the meantime, listen to our three-part series on the Mayflower’s history, because we didn’t even scratch the surface in this newsletter! (The events we describe run the gamut from inspiring—think FDR—to salacious—think JFK—to unprecedented.)

We don’t know when, but we will definitely be returning to Washington, D.C., (and hopefully the Mayflower!) to explore more of its captivating history.